New Information about the Amboise conspirator Châteauneuf, a.k.a. “Velours Nose”

date posted: December 24, 2024

A major component of Season of Conspiracy involved identifying participants in the Huguenot conspiracies of 1560 and their life course both prior to and following their engagement in these enterprises. One captain of the Amboise conspiracy whose precise identification has long puzzled historians is the man first identified by Louis Regnier de La Planche as the captain for Provence and Languedoc, “Chasteauneuf.” According to La Planche and the many historians who have followed him, he was designated as the captain of the conspiracy for Provence and Languedoc at the preliminary planning assembly held in Nantes on February 1, 1560. He then traveled to Provence to organize the effort in that province, which he did by summoning a “synod” in Mérindol to which representatives of sixty churches sent representatives. “Chateau Neufz” also appears at several points in the deposition of Gilles Triou about the conspiracy-related activities in Lyon that I used as a key source in Season of Conspiracy. This document reveals that he passed through Lyon twice in early 1560, first stopping there to recruit members of Lyon’s Reformed church for the initial Amboise conspiracy on his way to the Nantes assembly, then again on his way back to tell those he had recruited of the decisions taken at the meeting. He showed up again in Lyon on September 1 of the same year for the meeting held in the upper-story apartment of the merchant Pierre Terrasson at which the final preparations for Maligny’s planned surprise of the city were made and then hastily cancelled. Triou’s testimony provides as well a noteworthy detail about Châteauneuf’s physical appearance: he wore “some black taffeta on the tip of his nose where he cut it.”

Because Châteauneuf or its Occitan equivalent “Castelnau” was such a common name for a seigneurie at the time, historians of 1560 conspiracies have so far been able to offer only tentative identifications of just which of the many Châteauneufs who lived in France at that time played this important role in the preparation of the Amboise conspiracy and its Lyonnais sequel. In La conjuration d’Amboise et Genève, Henri Naef suggested that it might be Charles de Châteauneuf, seigneur de Mollèges, a Protestant conseiller in the Parlement of Aix who was among the judges of that court who thought it prudent to leave the city after the failure of a Protestant plot to seize it connected to the Amboise affair, and who also can be placed in Geneva in January 1563, when he served as the godfather of a child born to another refugee from Provence living in the city. Arlette Jouanna and Hugues Daussy subsequently repeated this identification, with Jouanna adding a prudent “perhaps.” In Season of Conspiracy I suggested another possibility as well, Jean de Châteauneuf, écuyer, one of seventy Protestant refugees from Provence who signed a procuration in Lyon late in the First Civil War to raise money to carry on the fight. Because both identifications are uncertain, I did not say anything further about either of these Châteauneufs in the final section of the book, where I trace what is known about the subsequent fate of other participants in the conspiracies whose identification is more certain.

Since completing Season of Conspiracy I have come across a few further references that unquestionably refer to the Châteauneuf engaged in the 1560 conspiracies and provide a bit more information about his activity on behalf of the Protestant cause in the years immediately following. Among these are two signed letters that may provide the basis for a more positive identification of the Châteauneuf in question if a notarial contract or other document can be found that contains the same signature and provides further information about the man signing it.

The first document of interest is a letter that the Protestant Balthasar de Jarente (or Gérente), baron de Sénas,wrote to Antoine de Bourbon on December 25, 1561 (BnF, MS Francais 15875, fo. 440), warning of the “monopolles, seditions et assemblees” of certain Catholics of the province and offering the service of a hundred gentlemen of Provence willing to put their persons and goods at the service of the king and his authority, if the Catholics whom he accused of disloyalty rose up as he feared they soon would. The letter urges Antoine to learn further details about what these enemies of the crown were plotting by granting an audience to “le Sr de Chateauneuf, present porteur et fidelle serviteur de dieu, du roy et de vous.” This reference to a Châteauneuf with an established reputation of service to both the Protestant cause and to Anthony of Navarre suggests strongly that we are dealing here with the same Châteauneuf as the one who moved between Provence, Nantes and Lyon in 1560 amid conspiracies that looked to Anthony for leadership. It also places him in the entourage of the baron de Sénas or living in his vicinity.

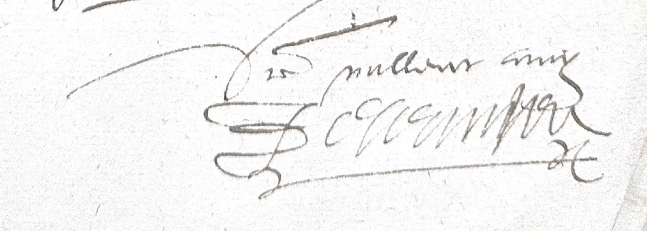

Several sources then speak of the passage through portions of Provence between February and June 1562 of a military man with the monicker “Nez de velours” or some variant spelling thereof. One of these sources, the Histoire ecclésiastique des Eglises réformées au Royaume de France (vol. 3, p. 384) even makes the link with Châteauneuf clear by identifying the person explicitly as “Chasteauneuf, surnommé Nés de Velours.” The first source is a deliberation of the Parlement of Aix held on February 6, 1562, the day on which the provincial governor, Claude de Savoie, count of Tende, and the crown’s special commissioner sent to repress the troubles in the region, Antoine de Crussol, entered Provence’s capital with troops in tow after having been refused admission for more than a week. At this meeting, one Catholic judge in the court informed his colleagues with alarm that “Nas de Velloux” had been spotted alongside Sénas and great Huguenot raider Paulon de Richieu, seigneur de Mauvans, among the troops accompanying Crussol and Tende (AD BdR, B 3648, fo. 354). The passage in the Histoire ecclésiastique then states that during the summer of 1562 he was given the task of guarding the perched village of Lurs amid the fighting between the troops under Tende’s protection and those commanded by Sommerive–unwisely, for “la lascheté d’un nommé Chasteauneuf, surnommé Nés de velours” allowed Sommerive to get past the stronghold overlooking the Durance and threaten Sisteron. Finally documents in the municipal archives of Forcalquier not only mention “Naiz de velours” as the captain of one of the Huguenot companies that entered that city on June 6, 1562, but confirm the Histoire ecclésiastique’s indication that he had soon thereafter been placed in charge of Lurs, located just to the east of Forcalquier. This confirmation takes the form of a letter written from Lurs on June 9 ordering the consuls of Forcalquier to prepare four thousand loaves of bread, a thousand pots of wine, and twenty sheep because the writer of the letter and his men were “sur notre partement avecq partie de notre camp pour nous acheminer pour aller trouver (?) notre adversaire et avecq l’aide de dieu le combatre.” Tied together with this letter in Forcalquier’s achives is a slip in a sixteenth-century hand that explains “estant nas de Vellouz au lieu de Lurs aiant certaines compaignies des huguenaulx, la ville de Forcalquier feust contraint pourter vivres aud. lieu” (AC Forcalquier, EE 33). Another letter in the same portfolio bears the same signature and was sent from Limans, to the northwest of Forcalquier, on June 21. Sixteenth century signatures are often hard to decipher, but if this signature is indeed that of “J Chateauneuf,” which is at least one plausible reading of it in my opinion, it could offer the key to better identifying this mysterious Huguenot warrior. Calling all local historians and genealogists in Provence: if you locate a contract or other document with this signature, please let me know!

I have as yet found no further reference to Nez de Velours that would tell us where he went and what became of him after he left Limans. As previously mentioned, he may be the same person as the Jean de Chateauneuf, écuyer, who subsequently took refuge in Lyon. That the author of the relevant portion of the Histoire ecclésiastique spoke so scornfully of his “lascheté” leads me to think that he either abandoned the Protestant cause or died in the interval between June 1562 and 1580, the year of the Histoire ecclésiastique‘s publication.